|

Unfortunately, I can't find a recording of this section

|

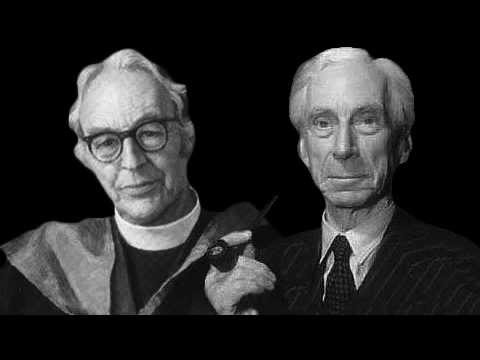

The BBC Debate was between religious believer F.C. Copleston and agnostic non-believer Bertrand Russell. The debate was in three sections, but only the first two form the extract in the Edexcel Anthology.

In this section, Copleston proposes support for the existence of God from religious experience. Russell responds by arguing for a subjectivist interpretation of religious experience. This section is much shorter than the lengthy discussion of the Argument from Contingency. |

The Argument from Religious Experience

Copleston introduces religious experience, not as a proof that God exists, but as a phenomenon that makes the existence of God more likely.

Analysis

Copleston proposes an inductive argument: he is not trying to prove that God exists beyond a shadow of a doubt; he is trying to show that the existence of God is more likely than not. He suggests that religious experiences suggest that people encounter some sort of supernatural force or being and this makes belief in God more reasonable.

Copleston identifies the important characteristics of religious experience like this:

Copleston identifies the important characteristics of religious experience like this:

- "A loving but unclear awareness": Copleston is describing mystical experiences or intuitions here; he later excludes "visions" which he thinks are too hard to distinguish from "hallucinations"

- "Irresistibly... transcending the self": Copleston is influenced here by Rudolf Otto and his description resembles Otto's idea of the Numinous

- "Something which cannot be pictured or conceptualized": Copleston seems to be influenced by William James, especially James' idea that mystical experiences are ineffable

- "Doubt is impossible... at least during the experience": This refers to James' idea that mystical experiences are transient and passive

- "There is actually some objective cause of the experience": This perhaps links to James' idea that mystical experiences are noetic, but also to the idea that religious experiences are COGNITIVE states of mind that give us knowledge of an external reality

Russell immediately draws attention to the private nature of religious experience. He contrasts experiencing God with seeing a clock in the room; anyone else in the room will also see the clock but they may not experience God.

Copleston admits this, but argues that religious experiences are in fact rather widespread (ubiquitous) and experiences that are similar to religious experiences happen to nearly everyone. He borrows an analogy from Julian Huxley, who compared religious experience with falling in love or appreciating art. Copleston adds that these examples assume that there is someone to fall in love with or a painting or poem to be appreciated - so religious experience suggests there really is a God who is being encountered.

Discussion

Copleston is using some well-known definitions of religious experience, burrowing (largely) from William James, but also from Rudolf Otto. He focuses on mystical/numinous experiences rather than religious visions for two reasons:

- It's easier to cast doubt on religious visions with naturalistic explanations (drugs, mental illness, brain tumours and head injuries)

- Mystical experiences seem to be linked to positive mental and spiritual health, whereas visions are often connected to mob violence, witch hunts and other unhealthy behaviours

|

However, it's interesting that Copleston's own definition excludes many of the most famous religious experiences in the Bible: Moses' theophany, Paul's Christophany, the Transfiguration of Christ, even the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. As a Catholic priest, Copleston is well aware of these important religious experiences. Yet he deliberately rules them out from his argument.

This partly because he doesn't want to appeal to revelation; he wants his argument to 'stand on its own two legs'. Perhaps it's also because he doesn't want Russell to be able to 'opt out' of this argument the way he seemed to while they were discussing contingency; Copleston doesn't want to give Russell the excuse to say 'I don't want to talk about that.' |

|

Russell's comment about the private nature of religious experience is an attempt to suggest that these experiences are SUBJECTIVE (they occur only in the believer's head) and not OBJECTIVE (which would be an encounter with something real, something that actually exists).

|

Russell is not correct in saying that these experiences are always private. There are corporate religious experiences too. A famous example is the Toronto Blessing, where Christian worshipers experience ecstasy, 'holy laughter' and spiritual healing.

The Toronto Blessing occurred in the 1990s, long after the BBC Debate, but similar experiences were reported earlier in the 20th century by Christians at the Azuza Street church in Los Angeles. However, this sort of corporate religious experience largely occurred in America and often in poor and Black churches, so Bertrand Russell (British, white, wealthy) might not have been aware it was going on. |

|

Since Copleston doesn't correct Russell on this, presumably he wasn't very aware of the revival of corporate religious experience going on among poor and Black Christians in North America either.

|

It's odd that Copleston draws in Julian Huxley for support. Huxley was the grandson of Charles Darwin's friend and defender T.H. Huxley and was himself a biologist and a defender of evolutionary theory. Julian Huxley helped start the British Humanist Association, which campaigns against the influence of religion in society (he also founded the World Wildlife Fund).

I can't find the original statement that Copleston refers to, where Huxley compares religious experience to falling in love. However, I suspect that Huxley would have said this to suggest there is in fact nothing supernatural about religious experiences - they are perfectly natural psychological experiences, like falling in love.

I think Copleston is perhaps reinterpreting (or 'twisting') what Huxley said, to suggest there IS something supernatural about religious experiences.

|

Whatever the context of Julian Huxley's original analogy, Copleston uses it to argue that religious experiences are objective experiences (of a real thing, God) rather than subjective experiences (of an imaginary thing).

The discussion gets interesting when Russell starts comparing religious experiences to people having intense relationships with fictional characters in stories or novels.

Analysis

Russell makes the odd connection to the idea that people in Japan fall in love with characters in romantic novels and commit suicide out of despair - and that Japanese novelists rate their success as writers on how many of their readers do this.

I don't know where Russell got this odd snippet of cultural stereotyping from - but the current phenomenon of Japanese youths falling in love with fictional characters is discussed below.

Copleston agrees that characters we get to know through books can be very influential - he admits himself to being guided in his life choices through reading two biographies of famous people.

We don't know which biographies Copleston read that had such a big effect on him, but we can guess. Copleston converted to Catholicism when he was 18, which caused a strain in his Anglican family. Presumably a biography of a famous Catholic saint inspired him to convert - and based on what he says later we may guess that it was a biography of Saint Francis of Assisi.

|

Copleston thinks there is a real difference between mystical experience (of God) and aesthetic experience (of a character in a book - or a film, TV show or video game in the 21st century). He accepts that there are "deluded people and hallucinated people" who can't tell the difference between fantasy and reality. However, he thinks that religious experience is different from that. He gives the example of St Francis of Assisi, whose life was guided by powerful mystical experiences and who demonstrated "an overflow of dynamic and creative love".

Although he doesn't say it explicitly, Copleston is contrasting a sick and deluded mindset that is completely subjective and leads people to suicide with a healthy mentality based on an objectively real encounter with God that leads people to lead loving and transformative lives - people like St Francis. |

|

Russell reminds us that he's an agnostic not an atheist - and that he's not 'dogmatic' either.

Ouch! Did all those times Copleston accused him of being 'dogmatic' during their discussion of contingency get under Russell's skin?

Russell points out that not all mystics are like St Francis. Many mystics also claim to experience the presence of "demons and devils and what not". Russell is perhaps thinking of the sort of people who feel tormented by the Devil, who feel God is telling them to kill witches or go on Crusades, or just people whose mystical experiences also contain a lot of rubbish that turns out to be untrue,

Unfortunately, these mystics speak with "exactly the same tone of voice and with exactly the same conviction" as people like St Francis. How are we to tell good mystical experiences from bad ones - because (as far as Russell is concerned) there clearly are bad mystical experience out there?

Unfortunately, these mystics speak with "exactly the same tone of voice and with exactly the same conviction" as people like St Francis. How are we to tell good mystical experiences from bad ones - because (as far as Russell is concerned) there clearly are bad mystical experience out there?

Discussion

The importance of fictional characters for the debate on religious experience is going to return at the end of this extract. In the meantime, a 21st century version of what Russell describes certainly exists. A subculture of Japanese youngsters called otaku use the word "waifu" to refer to the characters from anime (Japanese cartoons) who they see as their 'wives'. In fact, there are examples of Japanese young men officially marrying female characters from video games. There have even been examples of suicides brought about by relationships with 'waifu' characters.

|

|

|

A news item on waifu and a Young Turks discussion of the phenomenon. Of course, these behaviours aren't restricted to Japan - it's just that the Japanese have words to describe these relationships that are widely used in Internet geek culture.

Copleston's idea that mystical experience can lead to a positive lifestyle links to William James' concept of 'Saintliness'. For James, a saintly character is one where "spiritual emotions are the habitual centre of the personal energy". James states that saintliness includes:

An immense elation and freedom ... A shifting of the emotional Centre towards loving and harmonious affections - William James

F.C. Happold, talks about the mysticism of love and union which is a longing to escape from loneliness and the feeling of being ‘separate’. Happold believes that we have a desire to be part of something bigger than ourselves and religious experience gives us this.

|

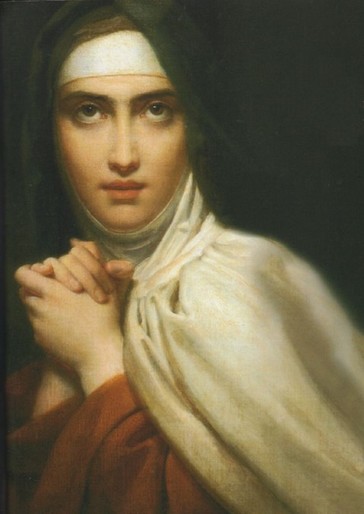

Russell is quite right to point out that mystical experiences can also be horrifying encounters with the Devil. In the Bible, the Book of Revelations is one long religious experience, much of which consists of the horrors of Hell and the activity of Satan on earth. Famous mystics like St Teresa of Avila who recorded many of the "pure type" of religious experience that Copleston approves of also reported frightening encounters with the Devil.

There's no way religious believers can just dismiss books of the Bible, or pick-and-choose from the mystical experiences of the great saints of the past. Yet if we accept that their religious experiences were encounters with an objective reality, then we have to accept the literal existence of demons and devils. Bertrand Russell doesn't believe in demons and devils, so instead of making God more likely for him, these religious experiences seem less trustworthy. Students will have to decide for themselves whether reports of demons and devils from people who report (otherwise very persuasive) religious experiences counts against those experiences being true. |

Russell and Copleston discuss 'demonic' religious experiences until Russell announces that the you can't judge religious experiences to be true just because of the effect they have on someone's behaviour.

Analysis

Copleston argues at first that these 'demonic' religious experiences are really "visions" and don't count, but Russell argues that people have "purely mental experiences" where they think a devil is tempting them or oppressing them. Copleston replies that there's still a difference between a 'demonic' religious experience and a mystical experience of God. He thinks this difference is in the effects it has on the person's life.

Copleston has already described the "overflow of dynamic and creative love" in the life of St Francis. Now he describes a non-Christian mystic. Plotinus was a Greek pagan mystic of the 3rd century. His ideas were very influential on later Christians and Muslims. We know about Plotinus' life from the writings of his student, Porphyry. Although he was a pagan, Plotinus believed in one God and devoted himself to mystical experiences. Copleston draws attention to Plotinus' "kindness and benevolence" and links this to his mystical encounters with God.

This prompts Russell to come up with one of his best put-downs:

This prompts Russell to come up with one of his best put-downs:

The fact that a belief has a good moral effect upon a man is no evidence whatsoever in favour of its truth - Bertrand Russell

Copleston tries to argue against this in two ways:

- There is a link between the truthfulness of a belief and its moral effect if the belief actually causes the moral effect. For example, believing in a loving God might cause you to be more loving to others.

- A moral life is good evidence that a person is sane and truthful, which makes us more likely to trust that their religious experiences are true.

Russell is having none of this. He points out that he's had inspirational experiences in his own life that led to him him making good decisions. He doesn't think those experiences came from something outside himself (like God). Even if he had thought that, the fact that these experiences had good effects on him wouldn't have proved he was right.

Discussion

Copleston is on the backfoot here. He struggles to explain to Russell how a "pure type" mystical experience differs from a 'demonic' religious experience, then he struggles to explain how the good side-effects of a belief can give us any reason to suppose a belief is true.

Russell has a strong point. A lot of people have false beliefs that enrich their lives:

- A man may believe his wife is faithful and count himself lucky to be married to her, while really she is cheating on him

- A woman may believe herself healthy and engage in lots of valuable projects, when really she has a terminal illness

|

Psychology tells us about the Placebo Effect, which is when someone believes (falsely) that a medicine will do them good, when in fact they have been given a dummy pill. The sheer strength of their belief means they feel less pain and heal quicker. The Placebo Effect is so powerful that when drugs companies are testing new medicines they have to include a 'Placebo Conditions' of people who are given a fake drug so that they can check that the real drug does more good than just belief on its own.

|

These examples reinforce Russell's point that false beliefs can lead to good effects - so we can't be sure that a belief is true just because it has good effects. Similarly, there might be true beliefs that have terrible effects:

- A man who believes his wife is cheating on him might be driven to depression, alcoholism and suicide, but that doesn't make his belief false

- A patient told by a doctor that she has a terminal illness might be consumed by bitterness and despair, but that doesn't make the diagnosis wrong

|

Copleston's position isn't entirely doomed. There's a long tradition in Christianity of testing religious experiences according to 'the Fruit of the Spirit'.

But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control - Galatians 5: 22-23 Many religious believers feel there is something special about genuine religious experiences - that they are immediately recognizable and distinctive. In other words they are SELF-AUTHENTICATING. William Alston points out that religious believers use external tests to verify religious experiences. For instance, Catholics have developed a system of tests to distinguish between real experiences of God and false or delusional experiences (coming from the Devil).

|

Russell and Copleston discuss how people can be positively influenced by characters in books who don't really exist.

Analysis

|

Russell introduces a character from Ancient History called Lycurgus. Lycurgus is a legendary character but he's described by the Roman historian Plutarch as a real person. He's supposed to have lived around 900 BCE in Ancient Greece. He is supposed to have organised Sparta into the militaristic society that we know from films like 300 (2006, dir. Zak Snyder). He was also incredibly fair-minded and would give up the kingship of Sparta freely so that the rightful heir could be king.

|

Russell imagines how a schoolboy might read about Lycurgus and be really inspired by his story: perhaps to get involved in politics or join the army, or to visit Greece or get great grades in Latin, or simply to be a better person. If the schoolboy found out about Lycurgus from reading Plutarch in Latin lessons, he would think Lycurgus was a real person who lived centuries ago. But in fact, Lycurgus is just a legend. But the boy has enjoyed a beneficial effect because he BELIEVED Lycurgus was real. This is a bit like the Placebo Effect, but with role models instead of medicines.

It says a lot about Russell and Copleston's backgrounds that they think it's perfectly normal for schoolboys to be inspired by the stuff they read in Latin lessons. Russell was very upper-class and was educated at home by private tutors; Copleston went to a top boarding school. Other schoolboys might have been more inspired by characters from comics or popular films: Robin Hood and King Arthur would be good examples of a character a young person might be inspired by, thinking they really existed in the past when in fact they were legendary.

The point of all this is that God might be a character like Lycurgus. Someone reads about him in a book (the Bible) and believes him to be real and gets very inspired and there are all sorts of positive effects in the believer's life. But the whole time, God might not be real.

Copleston has an interesting reply to this. He agrees with Russell that people can be inspired by fictional characters - and by fictional characters that they wrongly think are real characters. However, he thinks the mystic is in a different situation, The mystic thinks he is encountering "the ultimate reality". This is completely different from thinking about a very inspirational person, even a person who embodies some very important values..

Discussion

|

Ever since Arthur Conan Doyle wrote the Sherlock Holmes detective stories over a hundred years ago, people have been writing letters to the great detective at 221B Baker Street believing that he was a real person. The letters still arrive today, dozens every week from all over the world.

Clearly, people can be inspired by a non-existent character that they believe to be a real person.

|

Of course, in the 21st century Internet age, there are many religions based on fiction which the worshipers know to be fiction:

In an society where some people are Jedis, Bertrand Russell seems a bit quaint when he carefully picks out a fictional person that a reader might genuinely believe to be historical. In the 21st century, being fictional doesn't stop you being the focus of a religion. That's post-modernism for you.

The existence of blatantly fictional religions in the 21st century seems to back up Russell's idea that religion is really no different from identifying very strongly with a fictional character. However, it's worth noting that fictional religions like Jediism focus on the values behind the Star Wars films and this backs up Copleston's point that what people are being influenced by when a fictional character inspires them is the 'real value' that the character represents.

|

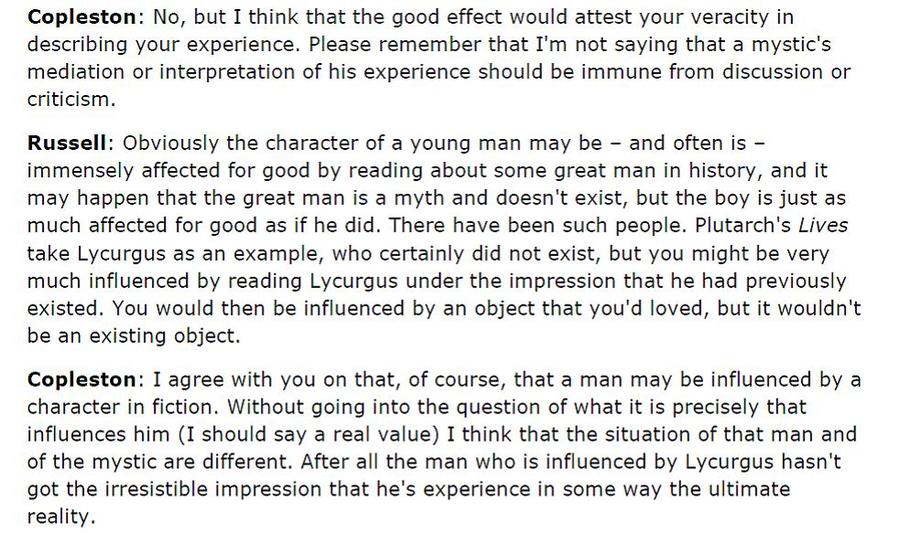

Copleston's point that mystics claim to encounter the "ultimate reality" needs investigating. The idea clearly resembles John Hick's idea of God as 'the Real' which lies behind all the various religious traditions. His Parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant shows how different religions can encounter the same ultimate reality and still describe it very differently.

Hick's thinking goes back to Immanuel Kant, who argued that there is the Phenomenon (reality as we perceive it through the senses) and the Noumenon (ultimate reality as it really is). Kant didn't believe that anyone could ever experience noumenal reality, but religious believers claim that the Noumenon is God and that God seeks out contact with humans. On this sort-of-Kantian view, a religious experience is a brief contact with noumenal reality, which is very different from an intensely imagined encounter with a fictional character. |

The Elephant is God (the 'ultimate reality') and the Blind Men are like mystics, having genuine encounters but reporting them differently

|

Russell and Copleston conclude with discussing the extent to which loving God is like "loving a phantom"

Analysis

Russell introduces the memorable phrase "loving a phantom" (a phantom is a ghost or an illusion) to describe someone who is inspired by a fictional or non-historical character (like Lycurgus). Russell suggests that religious believers are also 'loving a phantom'. They are inspired by a beautiful idea or a romantic story, like the stories in the Bible. It affects the way they live their lives - often (but not always) for the best - but, at the end of the day, there's nothing there. The phantom isn't real; it's just in their heads: it's a purely SUBJECTIVE experience.

Copleston makes an important correction. We don't fall in love with just any fictional character. There has to be something behind them, some value that they embody or reveal in their behaviour. Copleston suggests we love the character because we love the OBJECTIVE VALUE they represent. In fact, what we really love is the value itself. What sort of things are these 'values'? Copleston probably has in mind things like compassion, courage, devotion, glory, fairness, things like that. He claims these values are "objectively valid". Even though the fictional character only exists in our heads, the things the character represents aren't just in our heads: they're real.

Russell can't see the difference between this and responding to a fictional character but Copleston insists that Russell is wrong. Someone who loves a fictional character isn't just 'loving a phantom'; they are "loving what [they] perceive to be a value". A religious mystic is getting ahead of someone who is devoted to a historical or fictional role model; the mystic is having a relationship with that 'ultimate value' behind all those characters and role models - God.

Discussion

Copleston's conclusion is intriguing. For it to be persuasive, you need to believe in objective (or absolute) moral values. This is the idea that some things are morally good in their own right, for everybody, everywhere. If these absolute moral values exist, then they really might lie 'behind' the appeal of historical or fictional characters who embody them.

The idea that God might be identical with moral goodness was first proposed by the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato. In this Platonic view of things, anyone who loves goodness is loving God, who literally is goodness. God is the living reality behind inspirational characters in fiction (or in history, or in everyday life) - whether people who are inspired by those characters realise it or not.

This means that a mystic who has a direct experience of God is 'cutting out the middle-man' or 'going direct to the source' - enjoying an encounter with the 'ultimate value' that everyone else gets second-hand through role models, legends, superheroes and fictional characters.

The idea that God might be identical with moral goodness was first proposed by the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato. In this Platonic view of things, anyone who loves goodness is loving God, who literally is goodness. God is the living reality behind inspirational characters in fiction (or in history, or in everyday life) - whether people who are inspired by those characters realise it or not.

This means that a mystic who has a direct experience of God is 'cutting out the middle-man' or 'going direct to the source' - enjoying an encounter with the 'ultimate value' that everyone else gets second-hand through role models, legends, superheroes and fictional characters.

|

|

|

C.S. Lewis always intended that readers of his Narnia books should love Aslan and (he hoped) move on to loving Christ in real life, because Aslan symbolises Christ. J.K. Rowling put Christian messages and symbols in the Harry Potter books and has stated that readers are supposed to understand love, sacrifice and redemption (key Christian ideas) better through her novels..

Copleston's charming idea collapses if there is no such thing as objective or absolute morality. In other words, moral ideas might be nothing more than subjective ideas, just thoughts in our heads.

Unfortunately for Russell, he's already rejected this position. Remember? Right back at the beginning of the extract, Copleston challenged Russell to admit that, without God, there would be no objective values and Russell replied that, although he didn't believe in God, he thought there were (or at any rate, might be) objective values. This is going to make things very tricky for Russell in the final section of the debate, which moves onto the Moral Argument for the existence of God.

However, the Edexcel Anthology extract ends here. If you want to read on yourself and see how Russell copes with Copleston's challenge, try the file below:

Unfortunately for Russell, he's already rejected this position. Remember? Right back at the beginning of the extract, Copleston challenged Russell to admit that, without God, there would be no objective values and Russell replied that, although he didn't believe in God, he thought there were (or at any rate, might be) objective values. This is going to make things very tricky for Russell in the final section of the debate, which moves onto the Moral Argument for the existence of God.

However, the Edexcel Anthology extract ends here. If you want to read on yourself and see how Russell copes with Copleston's challenge, try the file below:

Most (but not all) critics think Copleston gets the better of Russell in this section, which perhaps makes the debate a 'draw' overall.

|

| ||